How Street Art Promotes Culture and Heritage in Belize

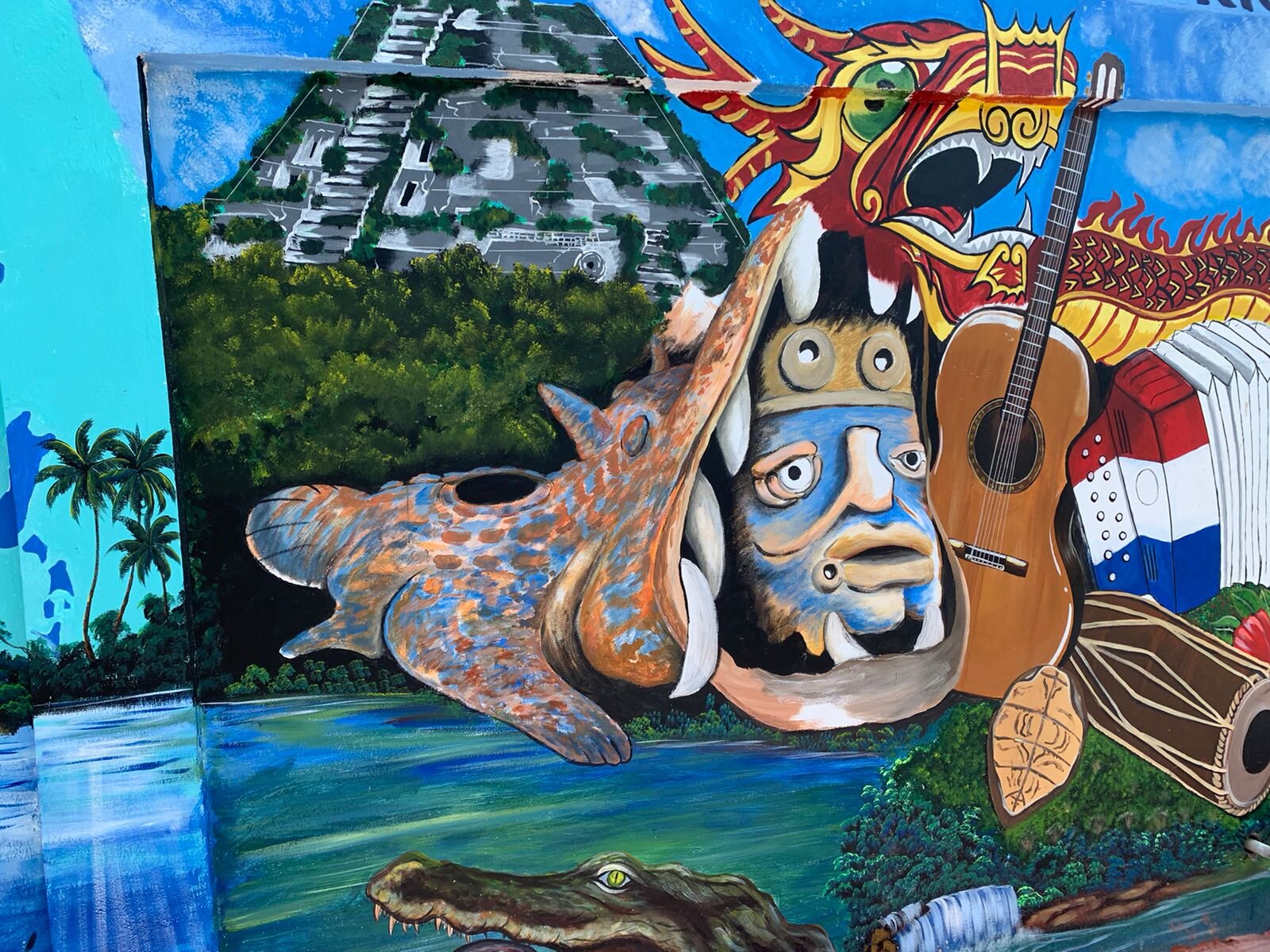

Mural from the University of Belize © Rebecca Friedel Juan

What is Street Art?

When you hear the word ‘graffiti,’ prehistoric cave drawings and archaeological sites may not be the first things that come to mind. The more modern interpretation of graffiti is counter-cultural ‘tagging’ that emerged during the late 1960s and early 1970s in New York and Philadelphia [1]. However, earlier forms of street art have always existed. In 2017, a ‘graffiti’ room was discovered at the El Castillo temple at Xunantunich, San Jose Succotz; this room was believed to be a training area for young Maya nobles [2]. Such a discovery showcases the ancestral origins of graffiti and, by association, public or street art right here in Belize.

It can be argued that without graffiti, street art would not exist. Graffiti consists of a range of designs [2]. from tagging to elaborate ‘pieces’ (from the word ‘masterpiece’), which often include complex letter styles meant to limit their message to a specific audience [3][4].

In contrast to the more private communication among graffiti artists, street art is known for having an explicit political or social message [3]. First, it is important to make the distinction between public art and street art. Public art includes various art forms—such as paintings, murals, and sculptures—and is typically commissioned by the government or a corporation. Like public art, street art also appears in public spaces and is available for public consumption. However, street art is usually not commissioned by a government [3], and therefore allows more space for creativity.

As a form of public or street art, murals are ‘open museums,’ typically painted on walls, where people can access heritage [5]. This art form can also “serve as a place of shared ‘memory’ for the community, contributing to the preservation and conservation of the community’s cultural heritage and providing opportunities for community involvement" [5]. With these definitions in mind, the significance of street art can be better understood.

Why Street Art Matters?

Think about your most recent encounter with street art in your local community: What feelings did the mural, graffiti, poster or sculpture evoke? What message did the artist(s) try to convey? How does the artwork impact the neighborhood both physically and socially? Regardless of your answer to these questions, the fact remains that street art is not neutral. Street art is ephemeral, attempts to be direct, and is highly visible “in order to attract as many people as possible to the message within a short frame of time” [3]. In countries like Belize, there is plenty of potential for street art to attract residents and tourists alike to learn about history and heritage [5].

It appears that there has been an uptick in the creation of, and appreciation for street art in Belize and across the globe. Why might that be? In the past, graffiti was solely associated with illegal and gang-related activities [6] [7]. As more cities began to embrace public art, street art’s appeal also grew. One of the more appealing aspects of street art is its ‘open-nature,’ making it more accessible and inclusive than art museums, which typically require waiting in line and paying an entry fee [8].

Street Art in Belize

Mural in Corozal Town, 2019 © Ella Békési

Debra Wilkes Gray, former coordinator of the Corozal House of Culture, and founder of Corozal Art in the Park (created in 2009) agrees that street art allows for community enjoyment along with its promising utilization as a tourist attraction. We recently interviewed Wilkes Gray about her work as the former director of the Corozal Street Art Movement (C-SAM). C-SAM’s story began in August 2017, with a small group of youth artists in Corozal Town who completed a mural painting workshop at the Corozal House of Culture facilitated by Belmopan artist, Kelvin Baizar. According to Wilkes Gray:

@C-SAM on Facebook

“The group wanted to create murals around town as a way of expressing themselves while advertising their skills. If a mural could put a smile on the viewer’s face, our mission would be accomplished. There is so much strife and struggle in the lives of so many of our countrymen and women; we wanted to uplift their spirits, even if it’s just for a few seconds. Art heals the soul.”

C-SAM runs completely on donations and support from the Corozal community, including wall space, paint and other art materials. The group has about 10 dedicated artists who have contributed over 50 murals in and around downtown Corozal. While they primarily focus on murals, C-SAM has expanded their skills by participating in graffiti and flacking workshops. ‘Flacking’ is the art of filling in holes or cracks in pavement with tile or glass.

Wilkes Gray attributes the rise in popularity of street art in Belize, at least partially, to the sheer talent of the street artists themselves. Wilkes Gray asserts:

“The appreciation has occurred due to the talent of our artists. You can’t deny a beautiful painting, can you? Belizeans have such a high percentage of in-born talent. It’s just now that they have the opportunity to share it with all of us.”

@C-SAM on Facebook - Flacking

When asked how C-SAM’s work relates to culture and heritage, here is what Wilkes Gray had to say:

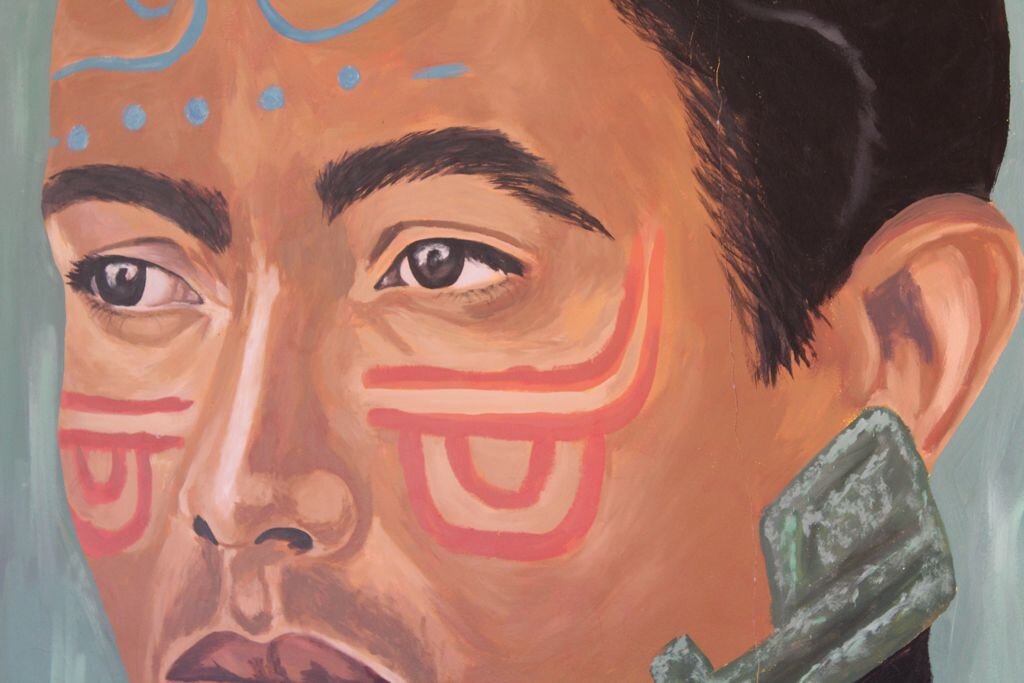

“C-SAM helps with the promotion and preservation of our town’s history as far back as ancient Chactemal. The famous Jade Mosaic Mask was discovered here and is a unique ‘brand’ for Corozal in which our artists have painted on a few occasions. Culture is the soul of the people. Culture is current [and] it shows in the art created today.”

Notably, C-SAM uses a portion of its own donations to support charitable causes. In the past, the group has given paint to the Diabetes Association of Belize - Corozal Branch for their storefront mural, the Corozal Organization of East Indian Cultural Heritage for their Masala Park benches, artisan Kimberly Griffith for her Souvenir Shop space, and to the Darina Garifuna Museum in Libertad Village for the painting of their new bathroom.

Muralism and street art play a role in other communities across Belize such as San Ignacio, where a newly established street art initiative known as the Locally Project was founded. Pablo Cambranes, founder of the Locally Project, notes the initiative was born from the need to beautify local businesses, highlight local artists, and preserve Belize’s culture with street art. Cambranes shares:

“[...] at the moment the [group’s] focus has been on murals that can easily be painted by one or more people because of the style. This makes it easier for anyone without much experience in painting to be a part of and feel involved in doing something for the community. Part of what makes each mural unique is that the location is also scouted to compliment and to further tell the story of the design. We hope to bring local and foreign attention to these small businesses and promote small destinations in Belize via the murals that will be painted there. I hope to one day have a team that would assist me in expanding the murals from the most northern community to the south of Belize.”

@Locally Project on Facebook

@Locally Project on Facebook

Echoing Wilkes Gray’s comments on why there has been a recent rise in street art, Cambranes expresses:

“Unfortunately, art has been a bit underappreciated in Belize. Covid brought back the creativity that so many of us had forgotten about. There has been a boom in creators as they turn to social media to showcase their talent, inspire others and ultimately come together to [allow] a renaissance in Belizean art to take place. As art continues [to] rise in Belize, we’ll be inspired by great artisans like Emilio Perera and Walter Castillo.”

@ Locally Project on Facebook

When it comes to graffiti, the National Institute of Culture and Heritage (NICH) hosted Graffiti Fest in 2019 and Corozal Graffiti Festival in 2020 (both initiated by Wilkes Gray), which featured other Caribbean and Latin American artists. Other street art festivals in year’s past have included the Placencia Sidewalk Art Festival, and Belize City’s Street Art Festival (or Street Fest).

The Municipal Mural Project

Mural from Orange Walk Town, part of the Belize @ 40 Municipal Mural Project, 2021 ©Alex Murrillos

Perhaps the most recent and vivid appreciation of public art is the Belize @ 40 Municipal Mural Project. To commemorate the 40th Anniversary of Belize’s Independence, the National Celebrations Committee (NCC) commissioned this unique project. This project involved 40 municipalities and local artists coming together to depict Belize’s rich natural heritage and diverse culture. To view videos highlighting some of the municipal projects, you can visit the Government of Belize Press Office’s Youtube Channel.

Alexis Carrillo, one of the 14 artists involved in creating the Orange Walk mural, told us about his experience working on the project. During his time, Carrillo acknowledges:

“The best part was getting to know the creative and skilful minds of the other artists. They became like my family of artists who shared memories and laughter that will never be forgotten. Murals tell a story. Some say it is a waste of the artist’s time, but what many don’t know is that this helps the artist gain recognition nationally and internationally.”

Each artist was charged with coming up with their own ideas centered around the September celebration theme. The group then reconvened and combined their ideas to form one sketch that was used as the final draft. Visit the Orange Walk Town Council Facebook Page to see the mural’s special effects at night.

@Alexis Carrillo (right), poses with Sapna Budhrani (left), President of NICH in front of Orange Walk’s Belize @ 40 Mural Project

Carrillo began painting at the mere age of 8 and has been pursuing this hobby firmly since 2017, being largely self-taught by watching and mimicking online videos. Carrillo mainly paints murals on canvas and participates in street art when he can relate to the artistic meaning behind the project, and of course, if there is a permit involved. For this artist, incorporating his culture and heritage into his artwork is an important aspect of cultural preservation. Carrillo explains:

“I always portray what I feel through my paintings; most artists do. I have created scenes from my Yucatec Maya culture that revives the past through my art. The same can be done with other cultures here in Belize.”

Belmopan’s Belize @ 40 Mural Project ©Rebecca Friedel Juan

Belmopan’s Belize @ 40 Mural Project ©Rebecca Friedel Juan

Dangriga’s Belize @ 40 Mural Project @Government of Belize Press Office on Facebook

As highlighted, street art often embodies a celebration of ethnic pride, neighborhood identity, and social and political histories [5]. This certainly rings true for the nation of Belize. Over generations, immensely talented Belizean artists have demonstrated their passion for various art forms.

When it comes to the future of street art in Belize, there are opportunities for networking among artists. Today, much networking seems to be informal through social media channels (i.e., Facebook and Instagram). A starting point would be for a national organization or government entity to compile a list of recognized street artists, and host workshops to help artists refine their skills. Additionally, art tourism is an area that can be explored further in Belize. In fact, “art objects can attract, entertain, and even educate the visitors, who may self-reflect and transform themselves through the art tourism experiences. Tourists may appreciate street art and graffiti as peripheral activities that enrich their trip experiences” [8]. For movements such as C-SAM, and the Locally Project, an associated goal is to inspire future generations of artists. Cambranes believes that:

“Right now is the perfect time for anyone to experiment on their own style, find their passions and be brave to merge them both to create something unique and of value to Belize. I hope that the Locally Project becomes a movement where young artists can look forward to collaborating with and serve as an ongoing community project where young Belizeans are encouraged to consider street art as a hobby.”

Regardless of what street art becomes for Belize, it currently facilitates the promotion and preservation of our natural and cultural heritage. In a sense, this is what it always has been and will continue to be.

See our Gallery of murals in Belize

Written by Kyrani Reneau

If you believe there are errors in this blog post, please contact volunteers.heritagebelize@gmail.com

References if you want to read more!

[1] Visconti, L., Sherry Jr., J., Borghini, S.,& Anderson, L. (2010). Street art, sweet art? Reclaiming the “public” in public place. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(3), 511-529. DOI: 10.1086/652731

[2] McCurdy, L., Brown, M. K., & Dixon, N. (2018). Tagged walls: The discovery of ancient maya graffiti at El Castillo, Xunantunich. Research Reports in Belizean Archaeology, 15, 181-193. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/37234419/TAGGED_WALLS_THE_DISCOVERY_OF_ANCIENT_MAYA_GRAFFITI_AT_EL_CASTILLO_XUNANTUNICH

[3] Cowick, C. (2015). Preserving street art: Uncovering the challenges and obstacles. Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America, 34(1), 29-44. DOI: 10.1086/680563

[4] McAuliffe, C. (2012). Graffiti or street art? Negotiating the moral geographies of the creative city. Journal of Urban Affairs, 34(2), 189-206. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9906.2012.00610.x

[5] De Miguel Molina, M., De Miguel Molina, B., & Segarra-Oña, M. (2018). Guidelines to stimulate use and social enjoyment. In Conservation, tourism and identity of contemporary community art: A case study of Felipe Seade’s mural “allegory to work.” Apple Academic Press.

[6] Schwender, D. D. (2016). Does copyright law protect graffiti and street art? (Jeffrey Ian Ross, Ed.) Routledge. DOI: 10.4324/9781315761664

[7] Wholf, T. (2013, November 3). As street art grows more popular, is it losing its edge? PBS NewsHour. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/as-street-art-grows-more-popular-is-it-losing-its-edge

[8] Yan, L., Xu, J. B., Sun, Z., & Xu, Y. (2019). Street art as alternative attractions: A case of the East Side Gallery. Tourism Management Perspectives, 29, 76-85.